The internal combustion engine will remain important

The internal combustion engine is a subject that has been described as nasty and outdated. In fact, it is not outdated at all – but an area of cutting-edge research that is an important part of a sustainable energy transition.

Jessika Sellergren – Published 15 May 2024

Martin Tunér is a professor of Internal Combustion Engines at the Faculty of Engineering (LTH) and he explains that a functioning and egalitarian society needs transport, something also stated in the UN's Global Goals. But how do we provide transport in a sensible and sustainable way?

“Electrification is essential for the future of transport, but it is not sufficient as the only solution. We need to work with several different tools at the same time to find the best solutions for the climate,” he says.

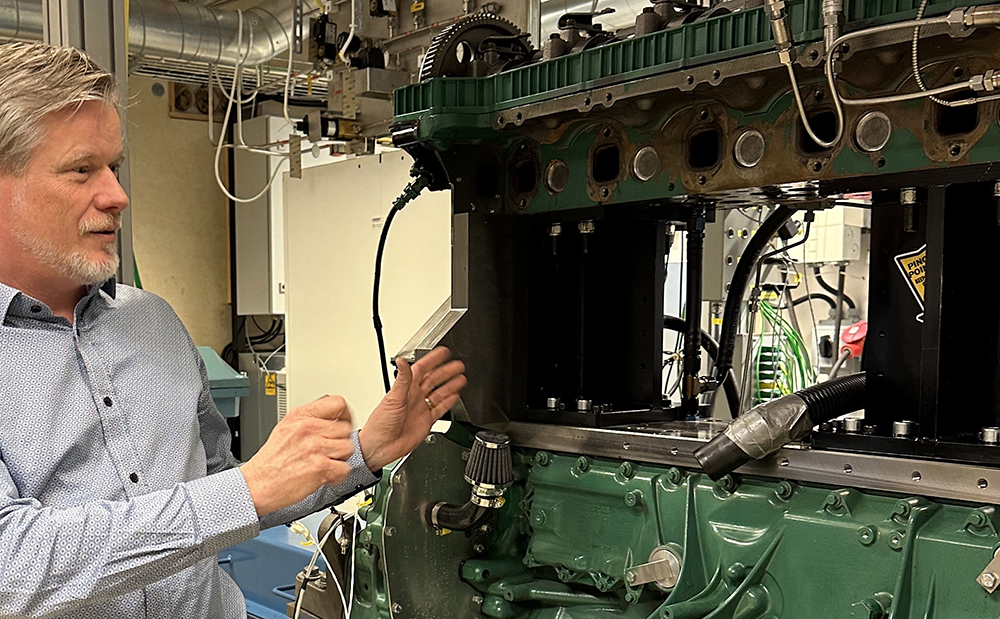

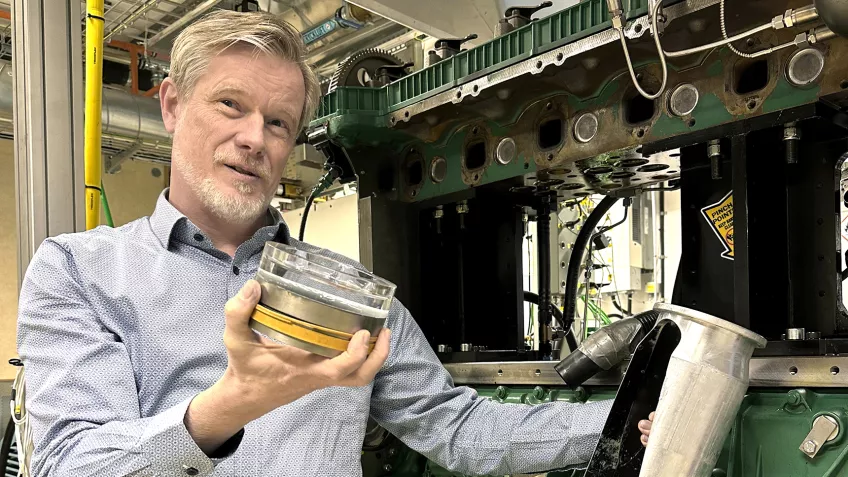

Martin Tunér is investigating how the internal combustion engine works together with new fuels and what kind of adaptations are needed. Photo: Jessika Sellergren

Martin Tunér says that the International Energy Agency (IEA) shows that if electrification proceeds too quickly, we will continue to be dependent on coal, a fossil fuel. Other energy sources such as solar, wind and hydropower are currently insufficient to meet the increasing demand for electricity that electrification brings.

“The transition needs to take place in a balanced way where we focus on several ways forward at the same time,” he says.

The internal combustion engine is included in that view of the future.

Few electrical vehicles

There are one and a half billion vehicles on the road around the world. Most of them are powered by an internal combustion engine and only a small proportion are electrified.

“What is going happen to all these vehicles? Should we continue to run on fossil fuels such as petrol and diesel, or should we develop fossil-free fuels that work with the engines we already have?”

The questions are rhetorical, because Martin Tunér confidently asserts that we should be working with renewable fuels for engines that are already in use. He also believes that we should further develop engines for those vehicles and machines that cannot be electrified or where electrification would have a greater negative climate impact.

“Internal combustion engines are a kind of omnivore that can be fuelled by many different things. The big problem is that they are mainly fuelled by fossil oil. So, it's not the engines that are the problem, it's the fuel we need to change.”

Bad reputation

But even though fuel is one of the largest problems, Martin Tunér describes a view of internal combustion engine research as outdated and bad:

“As combustion researchers, we have been told that what we do is nasty, evil and that we have been bought off by the oil companies.”

But Martin Tunér sees a trend towards a more nuanced view of research.

“The tone is different today, with a greater understanding of the challenge of phasing out fossil fuels, and that if we say no to renewable fuels or ban internal combustion engines, we will not be able to make the transition.”

Testing different engines

But how will the adaptation of the internal combustion engine work?

The answers to this question are emerging in Sweden's largest engine research lab. The engine lab at LTH consists of 14 test cells, each housing different types of engines, fuel cells and electric powertrains.

The lab houses engines for cars, lorries and ships whose technology is being rebuilt and tested with non-fossil fuels.

“We examine how the engine works with a new fuel, and what adjustments need to be made,” says Martin Tunér.

Some of the fuels that are currently the focus of research are hydrogen, ammonia and methanol, which can be produced using surplus electricity from wind and solar power. They affect the engines in different ways and require different adjustments to the mechanical engineering.

“It is interesting to see how these fuels, which can be produced and used with smaller climate impact, often also provide better engine efficiency than fossil petrol and diesel,” says Martin Tunér.

Smarter use of resources

But fuels are not the only thing being studied.

“We perform simulations and investigate how engines can be optimised and made more efficient for a robust and sustainable transport system. We also look at the overall environmental impact of a particular energy source through life-cycle analyses.”

A recurring theme for Martin Tunér is smarter use of resources. He earned his doctoral degree with a thesis on engine simulations, and even during his time as a doctoral student in the early 2000s he focused on resource use and a circular economy for transport.

“Planetary boundaries are exactly as the name suggests – boundaries. Resources are not infinite and must be combined wisely in order for them to be sufficient.. We humans also need to accept a different way of life if the planet is to last," he says.